Media diary

"Art, fascism, and the right to resist"

just something to take the edge off, I joke in a Letterboxd log of a recent CHILDREN OF MEN rewatch. On edge seems like an understatement of an appropriate response to the world today, where violence and cruelty and destruction are laid bare for everyone to see. As Mark Fisher reminds us in his review of Cuarón's prescient dystopia, "contrary to neo-liberal fantasy, there is no withering away of the State, only a stripping back of the State to its core military and police functions. In this world, as in ours, ultra-authoritarianism and Capital are by no means incompatible: internment camps and franchise coffee bars co-exist." The world never ends, it just (d)evolves.

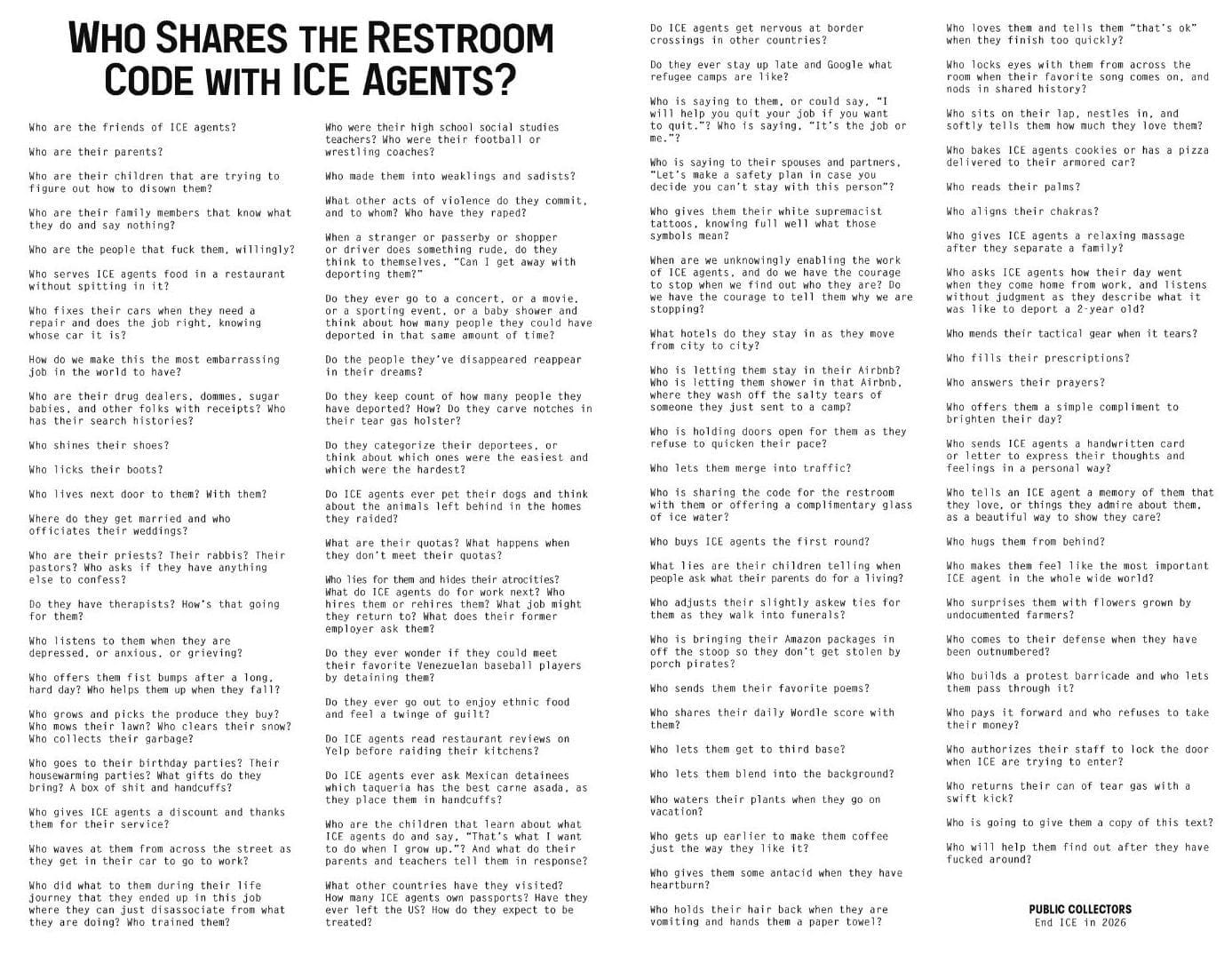

The editors of Equator describe the events of recent weeks as earthquakes, exposing "something rotten beneath the surface of liberal respectability: how elites participate in atrocity while maintaining prestige; how institutions supposed to safeguard justice in fact protect the powerful and exploit the vulnerable; how mass consent is secured through careful distribution of access and silence." Jasper Diamond Nathaniel similarly writes that this is the end of liberal Zionism, "the end of the story liberals told themselves: that power could be outsourced without consequence, violence compartmentalized, and moral language made to stand in for material reality."

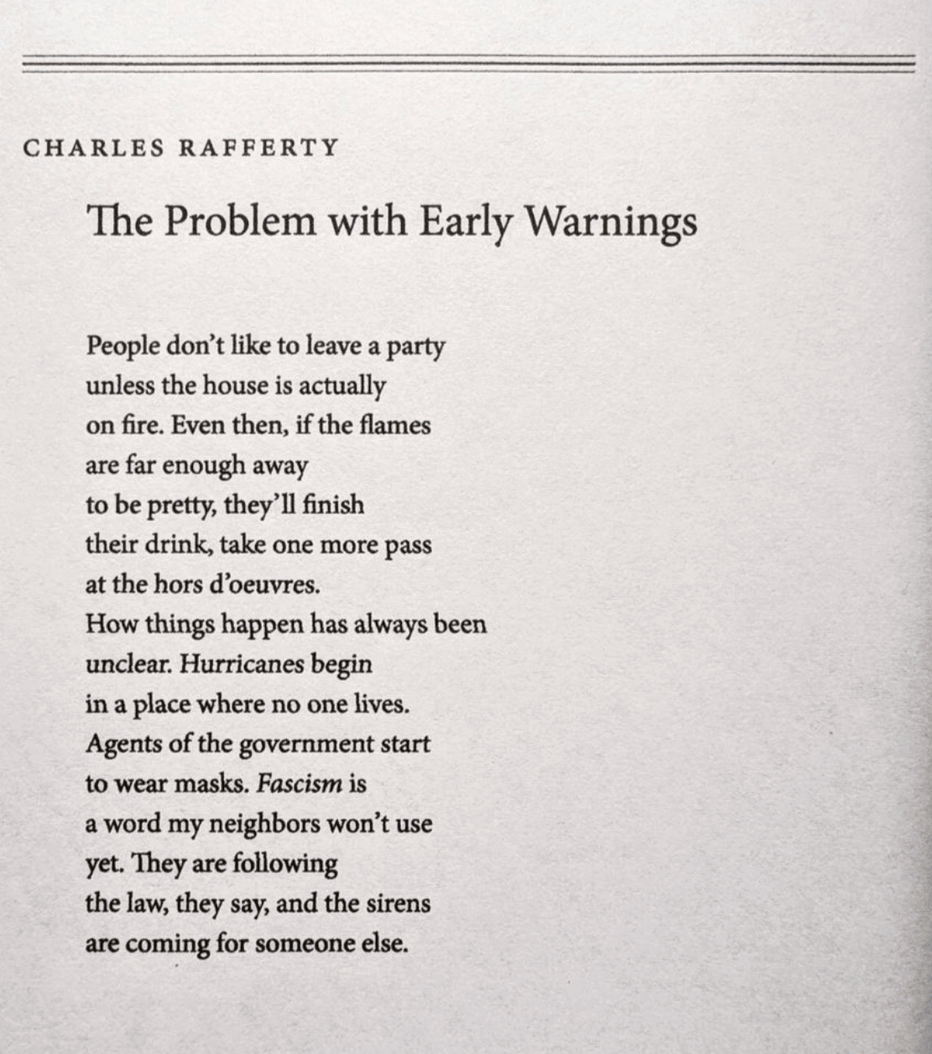

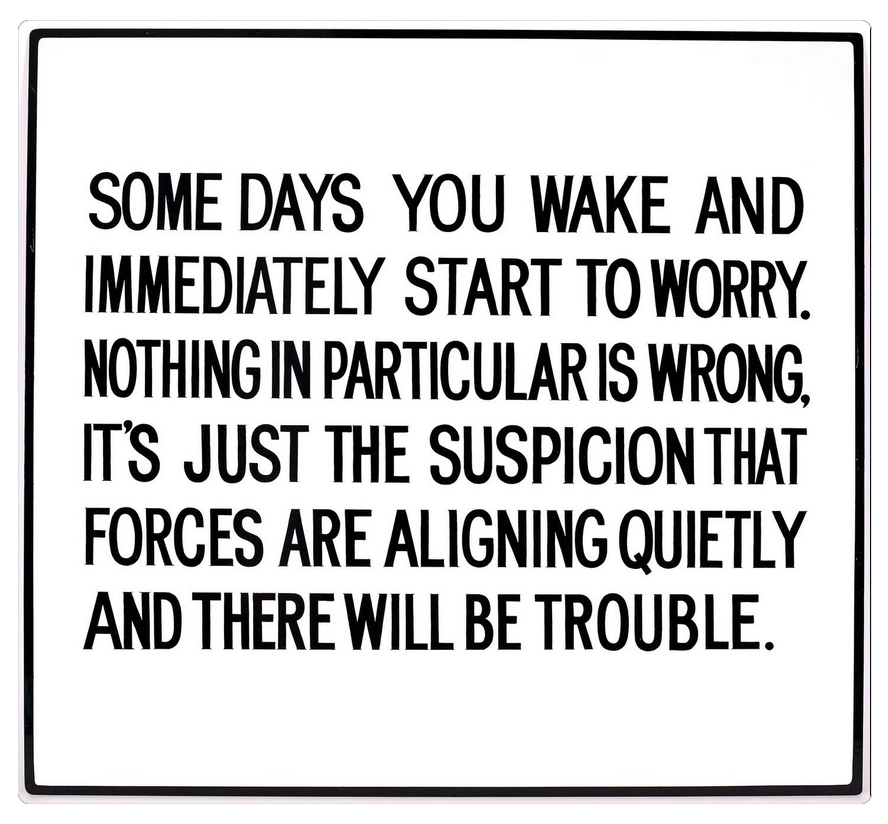

Twenty years after CHILDREN OF MEN, the gulf between those who are able to ignore our current reality–to see the franchise coffee bars but not the internment camps, to take the edge off–and those who aren’t seems to have only expanded. There are still many people who tell themselves stories in order to survive, for whom the fairy tales of liberal respectability and "rules-based order" still hold fast (including our democratic leaders). Fisher argues that "the normalisation of crisis produces a situation in which the repealing of measures brought in to deal with an emergency becomes unimaginable;" take a scroll through any social media platform and it immediately becomes evident that emergencies–earthquakes–are choking any chance of imagination (with a slop-bucket of AI programs hovering overhead, ready to help).

"The state produces death. Media allows for visibility and consumption of that death. Platforms algorithmically distribute the abundance of emotion and response to that death—from grief to dismissal to humor to outrage, in tribally sorted ways... This is the snuff film political economy in action," writes Sarah Thankam Mathews following the death of Renée Good. What will it take, she asks, to truly push back against the violence of the world, to see someone die on our screens and "claim them as human and grievable" when the immediacy of these images sensitize and anesthetize us simultaneously?

Similarly, in Image Control, Patrick Nathan argues that aestheticization of atrocity can numb us into thinking that simply consuming images is enough, that thinking it's terrible how things are is equivalent to thinking something must be done. Of course it isn't. When trained to consume everything—the news, the world, each other, death—as an image, to commodity identities and imaginations, all we are doing is "learning to discard and be discarded."

Desensitization from all these images of violence leads to an exhausted, impoverished, unhealthy electorate, a nation that no longer wants to lead, to think, to vote, or even to believe that things can change. Fascism feeds on this, this flattening of a complex reality which only requires indifference. In a world in which existence seems impossible, the masses, according to Hannah Arendt, begin "longing for fiction." Thought, critical or otherwise, becomes unnecessary (and again, the AI programs rub their six-fingered hands in glee).

Kleber Mendonça Filho's THE SECRET AGENT opens with an image of a corpse lying outside of a gas station, abandoned for days, covered with a cardboard sheet. It's an image that sticks with Wagner Moura's protagonist, but the proprietor of the gas station sees the body as merely a bureaucratic annoyance. The film, set in 1970s Brazil, is a self-described tale of "mischief" which, as per Cláudio Alves' review, "exposes the absurdities of life under authoritarian oppression, vivisecting the systemic rot that stinks fetid." Violence is commonplace, banal; the threat of it rears its head every day and hangs over every interaction; it gets turned into fiction and sold back to the masses as entertainment.

I hesitate to spoil the way the film takes shape, but from the very beginning it is clear that Filho's interest lies in memory, both personal and political. "I told you the story in the wrong order," a character confesses at one point. Another obliquely refers to the secret anti-fascist actions that she'll carry to her grave. A third swallows his identity in a heartbreaking act of assimilation. The secret "mission" of the titular agent plays out in an archive room, in search of something that deserves not to be forgotten. Rather than flattening history into a discrete, objective, easily-discarded image, Filho weaves torn and tangled threads of life together to create a narrative tied to our current time, a past inextricable from our present.

Back to that present, connecting Venezuela, Minneapolis, and Greenland, Nikhil Pal Singh argues that Trump does not transcend history, as most neoliberals would like to believe, but rather affirms it through America's "Homeland Empire." "Reversing this will require something more than a return to normalcy, particularly as the American security state tends to be accretive–recent history suggests that it only metastasises." We can't ignore the growing cancers of the past, nor can we turn our heads away from the deluge of images that aim to overwhelm us into inaction. We can't return to normal when military and policing are and have always been the norm, when everything else is stripped away and sold for slop. We have to remain mischievous, to remain human, to remember.